Below is a glossary of basic terms used in social network analysis. This list was first compiled for a webinar as part of the Getty Advanced Workshop on Network Analysis and Digital Art History in 2020, but the terms and definitions offered here should be useful to anyone starting out with a humanities network project.

Basic Terms

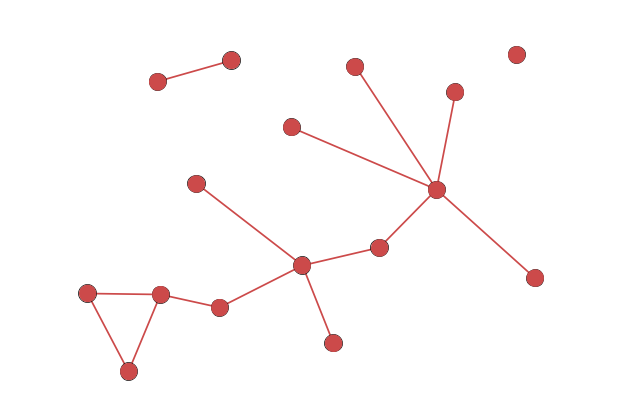

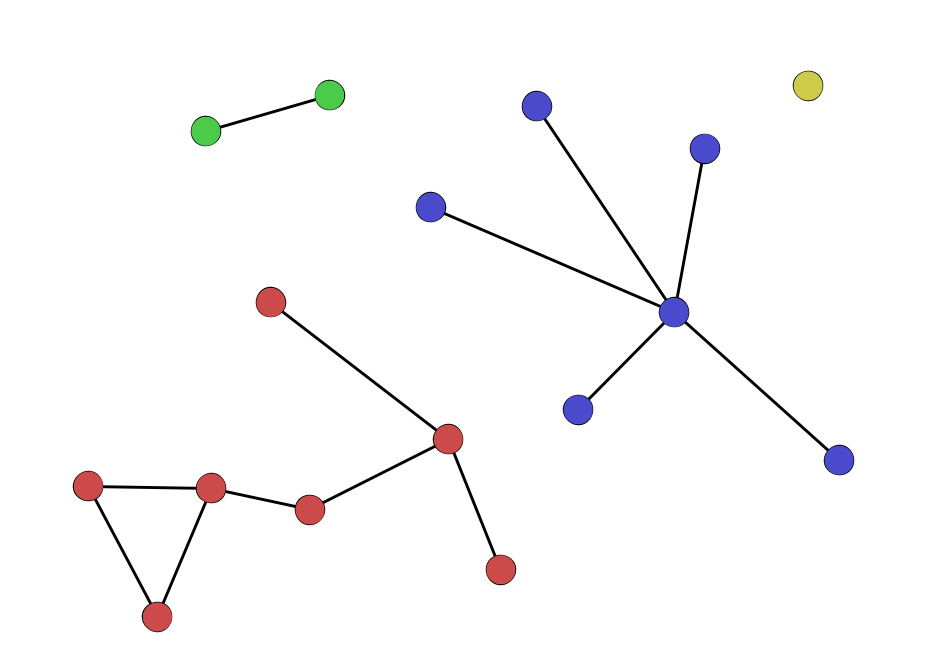

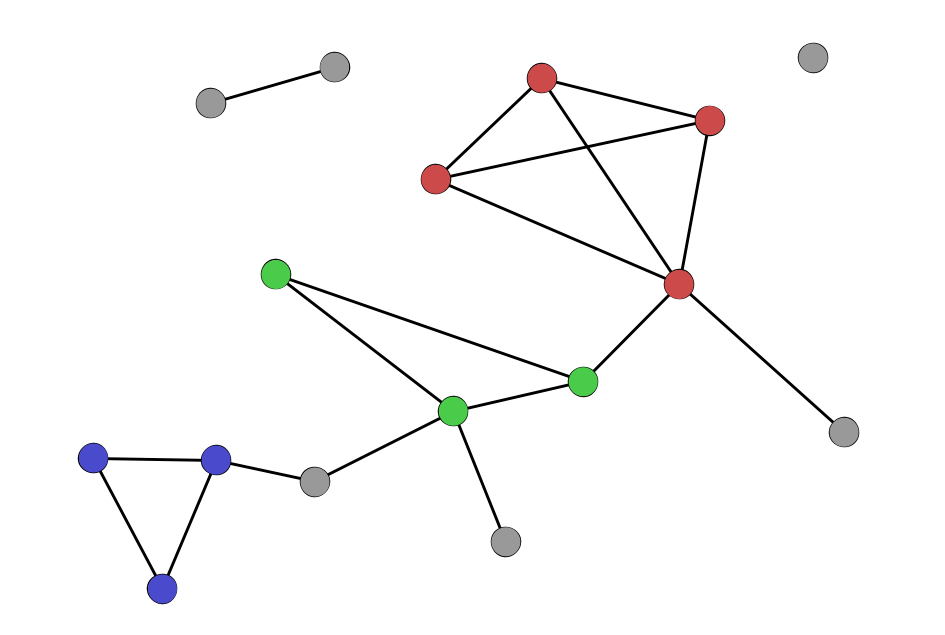

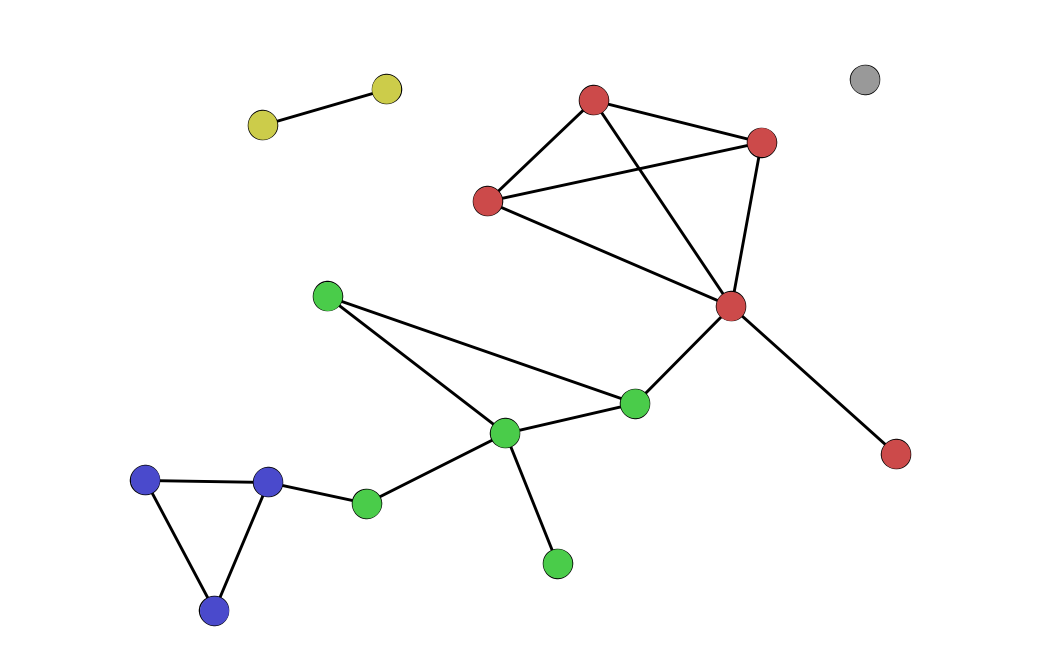

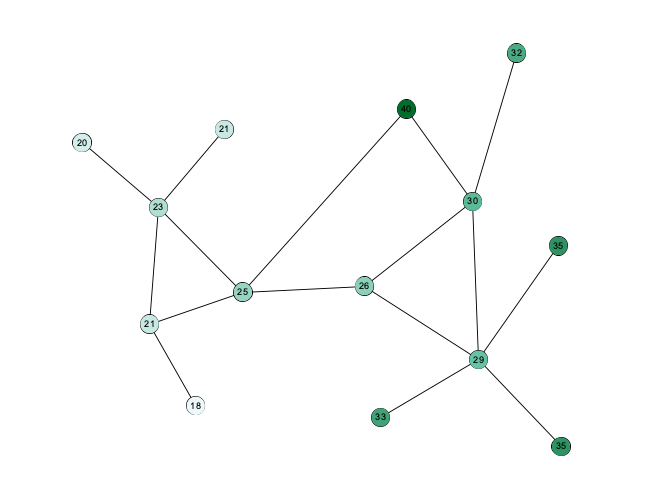

- node – any entity included in a network, also known as a vertex or an actor. Nodes are often represented as circles in network visualizations.

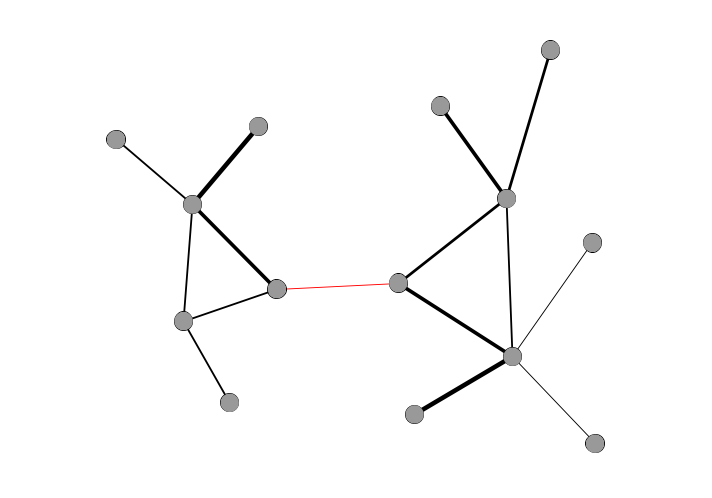

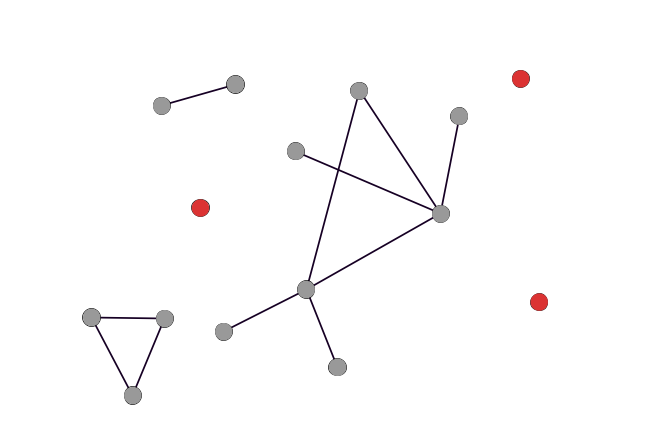

- edge – any relationship, also known as a link or a tie, that connects two nodes. Edges are often represented as lines in network visualizations.

- attribute – any property of a node or edge. Attributes can be either numerical (representing sizes, weights, and other measures) or categorical (representing types).

Properties of Edges

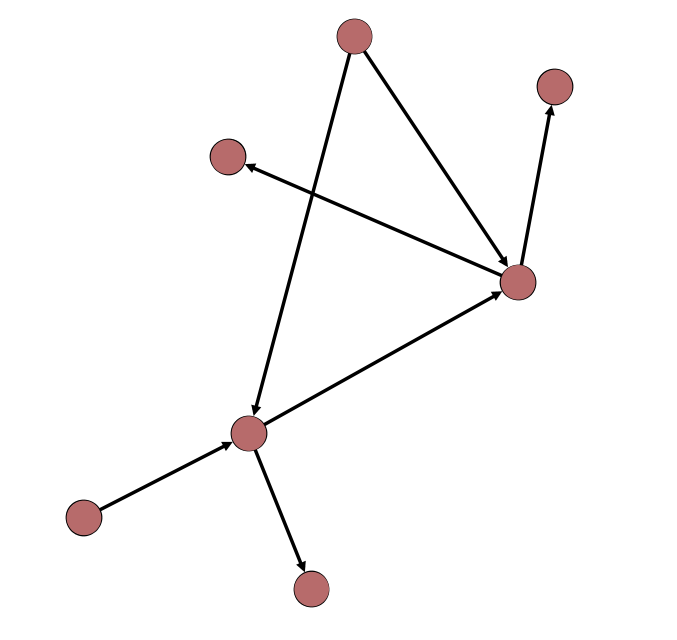

- directed edge – an edge that expresses a one-sided relationship, or any relationship where an exchange flows in one direction. A single correspondence, which has a sender and a recipient, is an example of a directed edge. Directed edges are usually represented as lines with arrows at one end. A network is said to be directed when at least one of its edges (and typically all of them) are directed.

-

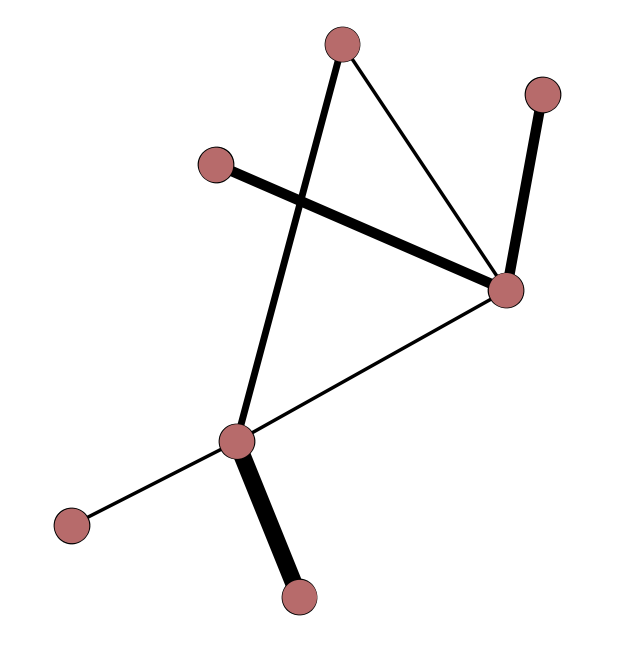

undirected edge – an edge that expresses a reciprocal relationship, where exchange flows in either direction. Friendship is an example of an undirected edge. Undirected edges are typically represented as lines without arrows. A network is said to be undirected when none of its edges are directed.

-

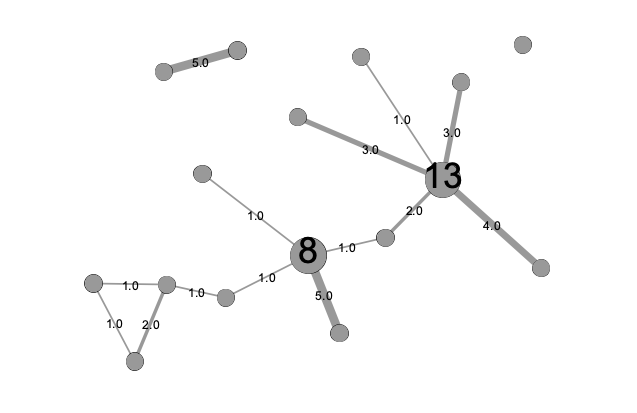

weighted edge – an edge with a value assigned to express the strength of a relationship. A correspondence where 8 letters were sent might have a weight of 8, while one with only 2 letters would have a smaller weight of 2. Edge weights are sometimes visualized as the thickness of an edge line. A network is said to be weighted when all its edges are weighted and unweighted when its edges indicate only the presence or absence of a relationship with no assigned weight.

Paths

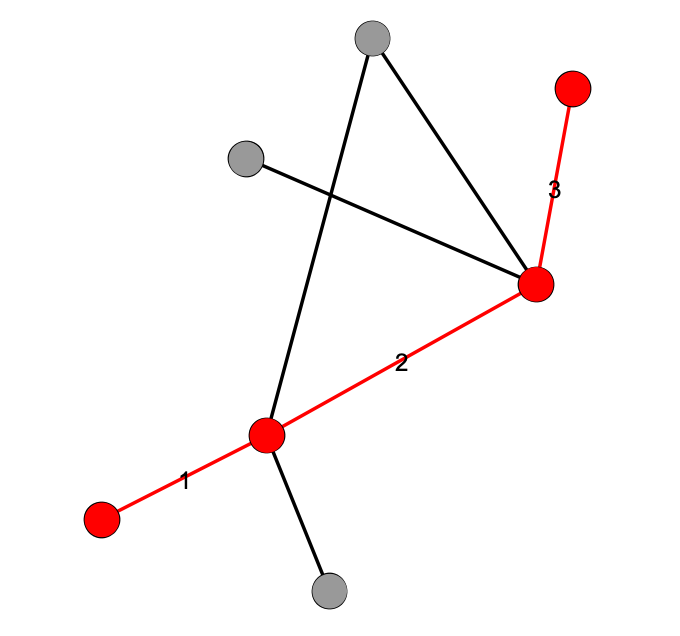

- path – a series of edges that connects two nodes that do not have a direct edge between them. Nodes three steps away from each other in a network have a path length of 3. A shortest path is the shortest possible route in the network between two nodes. The average of all shortest path lengths between every possible pair of nodes is a common network metric.

-

diameter – the shortest path connecting the two farthest-apart nodes in a network, i.e. the “longest shortest path” available in the network.

-

density – the number of edges in the network divided by the total number of possible edges in the network, if every node were connected to every other node. Density tells us how connected a particular network is.

Special Types of Nodes

- isolate – a node with no connections to any other nodes.

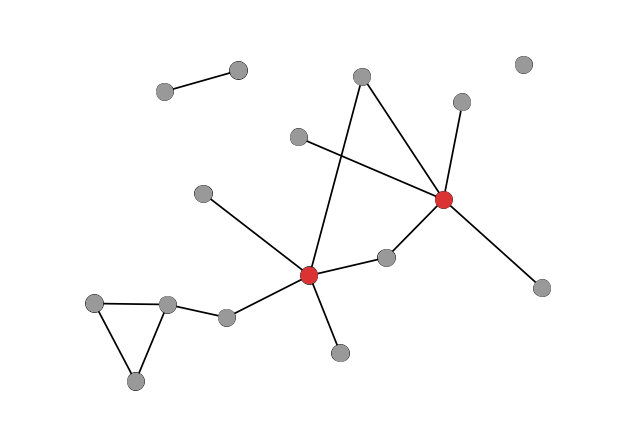

- hub – a node with many connections to other nodes. Hubs have very high degree (see below).

- bridge – a node that connects to otherwise disparate parts of a network. Bridges typically have low degree but high betweenness (see below).

- neighbor – a node directly connected to another, i.e. with a path length of just one edge.

Centrality

- centrality – a category of network metrics that attempts to understand how important a particular node is relative to the others.

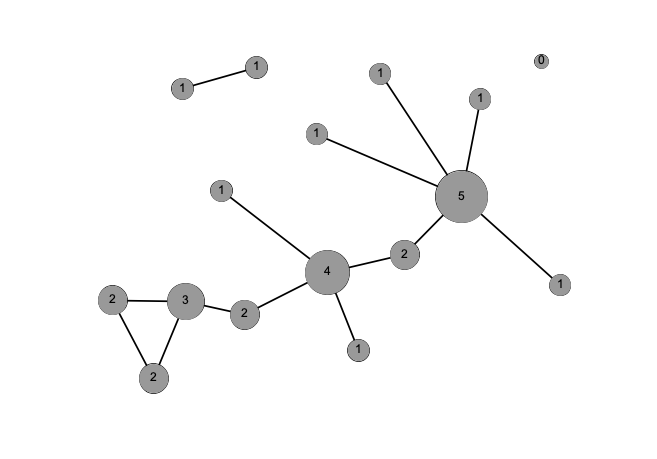

- degree – the number of connections (edges) a particular node possesses. Degree is the most basic measure of centrality.

- strength – in a weighted network, the sum of the weights of all a node’s connections. In weighted networks, some nodes can have low degree but high strength if they possess just a few highly-weighted connections.

-

betweenness centrality – in its simplest form, the number of shortest paths that must pass through a particular node. Betweenness centrality helps to measure how often any path in the network must go through a node and therefore can show if a node is connected to many disparate groups in the network.

-

eigenvector centrality – a centrality measurement based on a node’s degree and the degree of its immediate neighbors. A node can have high eigenvector centrality if it is adjacent to a high-degree node, even if the node itself doesn’t have very high degree. The Wikipedia article provides more mathematical detail on the eigenvectors and eigenvalues that make up this measure.

Multipartite Networks

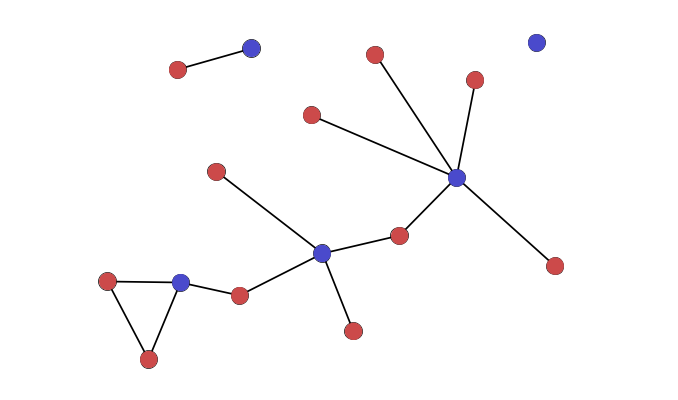

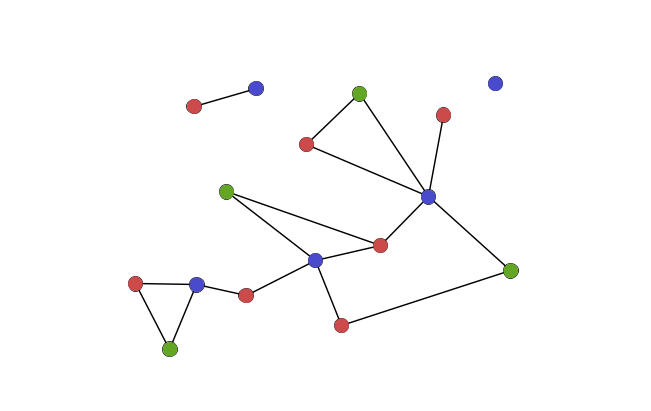

- unipartite/unimodal network – a network that has just one type of node. This is the most typical form of network explored in network analysis and the one for which most network metrics are designed.

- bipartite/bimodal network – a network with two types or classes of node, in which nodes of one class can only be linked to those of the other class. A network of books and their authors is an example of a bipartite network.

- multipartite/multimodal/k-partite network – a network with more than two types or classes of node, in which nodes can never connect to other nodes of the same class. (The k in k-partite simply represents any number.)

Groupings and Subsets

- connected component – a group of nodes that are linked by paths, i.e. any two nodes in the component will have at least one path between them. Networks are often made up of several such components.

- clique – a group of nodes where each node is directly connected to every other. Clusters are more rare than components, but can be used for understanding how connected or dense a network is.

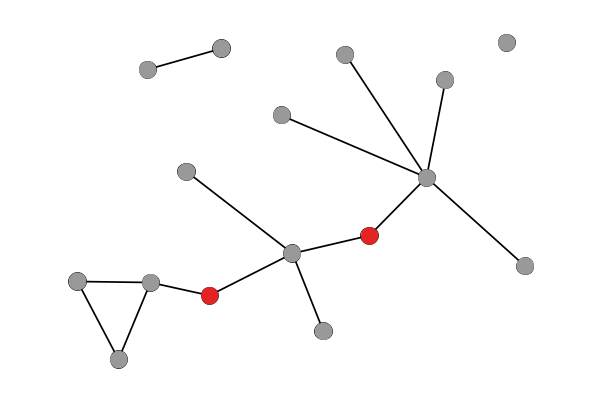

- clustering coefficient – the ratio of how many of a node’s neighbors are connected to each other, relative to the total number of neighbors.

- community – a grouping of nodes within a component that is usually more densely connected than the rest of the network around it. Communities can be defined several ways through a series of methods called “community detection.” The most well-known community detection method is modularity.

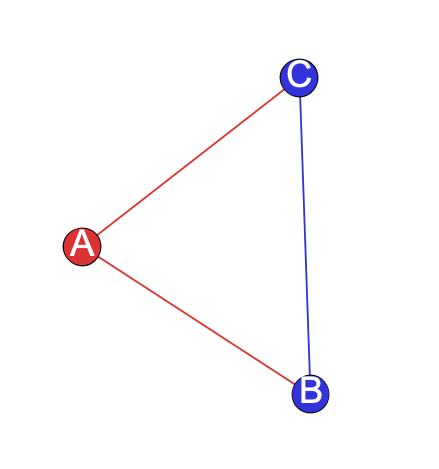

- triangle – a set of three nodes—A, B, and C—where A is connected to B, B to C, and C to A, forming a triangle. Clustering coefficients essentially measure the number of triangles of which any node is a member.

- triad – a set of three nodes—A, B, and C—where A is connected to B and C, but B and C are not connected. A triad is a possible triangle that is not complete.

- transitivity – the number of triangles in a network divided by the number of triads. Like density and average clustering coefficient, transitivity tells us something about how connected a graph is versus how connected it could have been. Higher transitivity creates more opportunities for cliques.

Visualizations

- adjacency matrix – a chart showing all the nodes of a network as rows and columns, with the cells of the chart containing either a 1 or 0 for the presence/absence of an edge (in an unweighted network) or the weight values of an edge (in a weighted network).

- adjacency list – a table where each row is an edge of the network listing the two nodes that are connected, as well as any attributes of that edge.

- node-link diagram – the most common form of network visualization, which typically represents nodes as circles connected by lines (for edges). Node-link diagrams can have many layouts, but the most common is the force-directed layout.

Key Network Principles

- small world network – a common kind of network with high density and low average path length. In a small world network, it’s easy to get from one node to any other in 6 or 7 “steps” or “degrees” (i.e. path length). This kind of network very often describes networks of human relationships, and the small world phenomenon is most famously described in the “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” parlor game.

- triadic closure – the likelihood that two nodes connected to the same node will also be connected to each other. I.e., if a node A has edges to node B and to node C, then B and C will likely also have a node between them. Triadic closure refers both to the general phenomenon and to the measure of how likely such closure is within a specific network.

- assortative mixing/homophily – the principle that “like attracts like.” If two nodes have other traits in common, they are more likely to be connected to one another. This is common in many types of networks but especially in human social networks.

- preferential attachment – the principle that a node with many connections is likely to gain even more connections, i.e. the “rich get richer” as a network phenomenon. Also common in human social networks. If a node is already a hub, new nodes that entire the network are more likely to connect to a hub than to other nodes.

- weak ties – edges with low weight that connect otherwise disparate parts of a network. In his now-famous essay “The Strength of Weak Ties,” Mark Granovetter asserted that low-weight edges are often the connections that hold a network together.